“It’s your decision.”

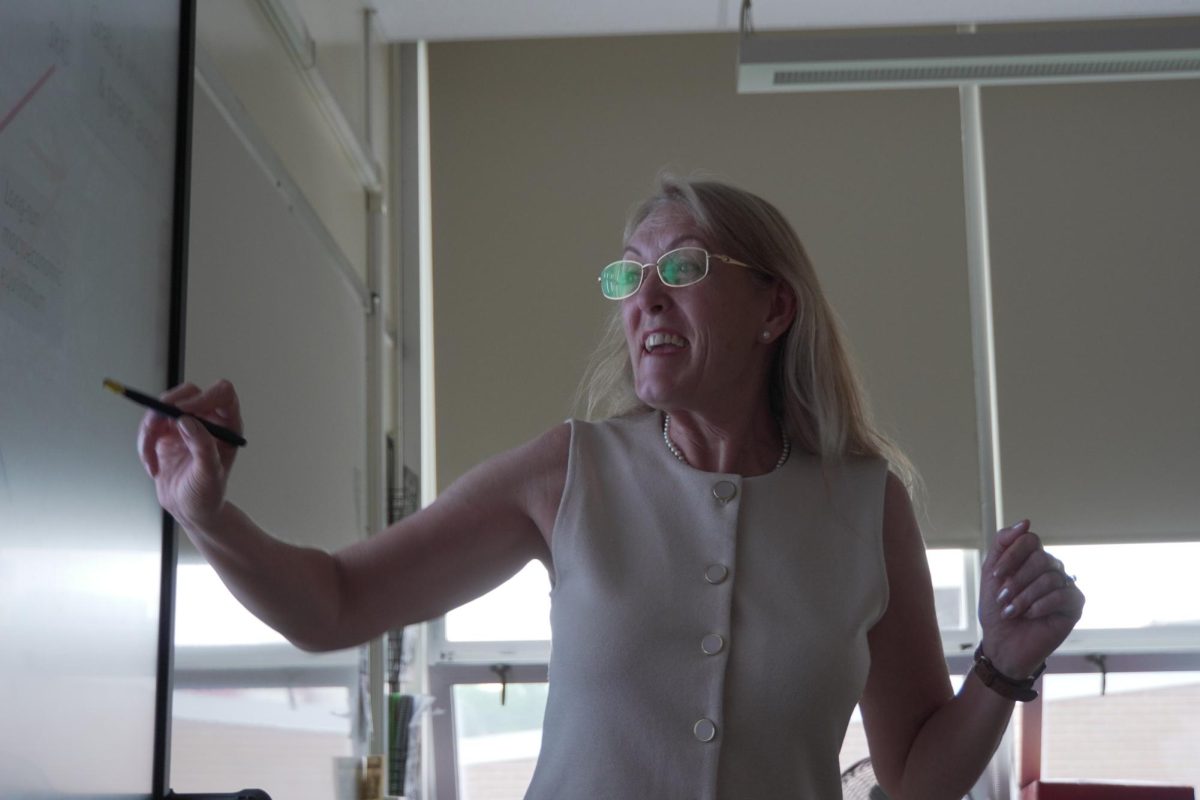

Dr. Sharon Anderson, an accomplished nurse practitioner currently serving as Associate Professor in the Division of Advanced Nursing Practice in Rutgers University, grew up listening to that phrase, designed to foster independence, confidence, and certainty in one’s career path.

But Anderson had a less traditional route to medicine, yet one that made her career all the more special. At first, she didn’t even consider medicine. Graduating high school, she decided to major in early childhood and elementary education but soon switched to advertising and public relations due to her former path’s competitive job market.

It was at that time when she had taken a job in waitressing that a curious stranger approached her. The woman, an avid tea-leaf reader, looked her straight in the eye, and said, “You’re going to be a nurse.”

“All that fell into place for me,” said Anderson.

From then on, Anderson never looked back. Finding her passion for medicine, she applied to nursing school in her junior year of college and got accepted into a three-year diploma nursing program. She highlighted this as the best education she could have gotten.

“You knew whether you like this field right from the beginning,” said Anderson. She lamented diploma nursing programs’ rapid disappearance as healthcare institutions continue to withdraw fiscal support.

“It’s sad that they don’t exist anymore,” said Anderson. “Right from the beginning of that education, I was immersed in clinical.”

She earned her masters in perinatal neonatal care, a practice revolving around the health of newborns and the period around birth, and soon settled into her clinical job at a hospital. From her years in the hospital, Anderson shared a few instances that demonstrated the complexity of the job. One premature baby, born with an omphalocele (intestines outside of the body), was struggling to survive in the NICU. Normally, babies with omphaloceles would undergo a surgery that placed intestines back into the body. However, this newborn was born with conditions that made it impossible for the surgery to be a success: underdeveloped lungs and a slowly coagulating bowel.

Anderson described the whole situation as “torturing the baby,” and eventually got the family to withdraw support. Feeling the weight of her decision, Anderson went to the autopsy of her patient and found her prediction to be right. Although heartbreaking experiences such as this one existed, gratifying moments also came about: Anderson shared that her favorite moments were immersed in creating connections between herself and her patients, and later, her students. These memories stuck with her for years after she transitioned from clinical to academia.

During her time in clinical, she switched from being a full-time practitioner to working in a genetics lab a few times a week, one of her numerous passions. Flexibility is one of the aspects she admires most about the field of nursing. Hundreds of pathways are open to nurses, including but not limited to research, like Anderson’s work in metabolic development (genetics), clinical practice (as a perinatal neonatal practitioner), and teaching (Anderson’s later career in academia).

“Nurses are severely underestimated,” she said.

After the hospital’s fiscal issues laid her off from work, Anderson applied to Rutgers to teach. She has worked in academia for about 17 years now, still pursuing her love of genetics development once a week. She cherishes the change she is able to see in her students and the connection she fosters with them.

Anderson, with her self-motivation and perseverance, shares that open doors line the hallway of nursing. Through over twenty years of experience, she has traveled from pathway to pathway, proving the versatility of her field and creating a fulfilling nomadic-style career for herself.

“I wear all these different hats,” said Anderson.