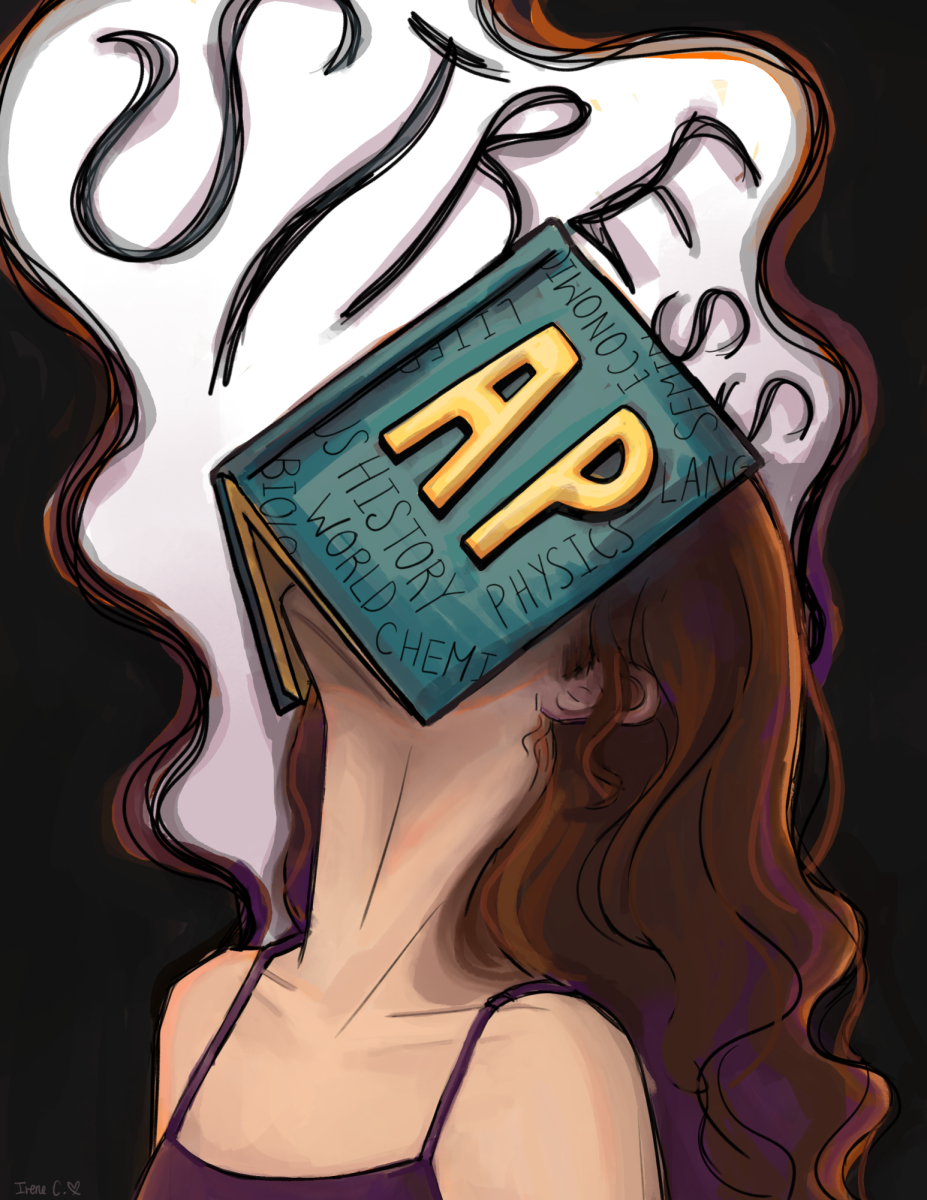

Editorial: Burnout—Man’s Greatest Fear

November 25, 2020

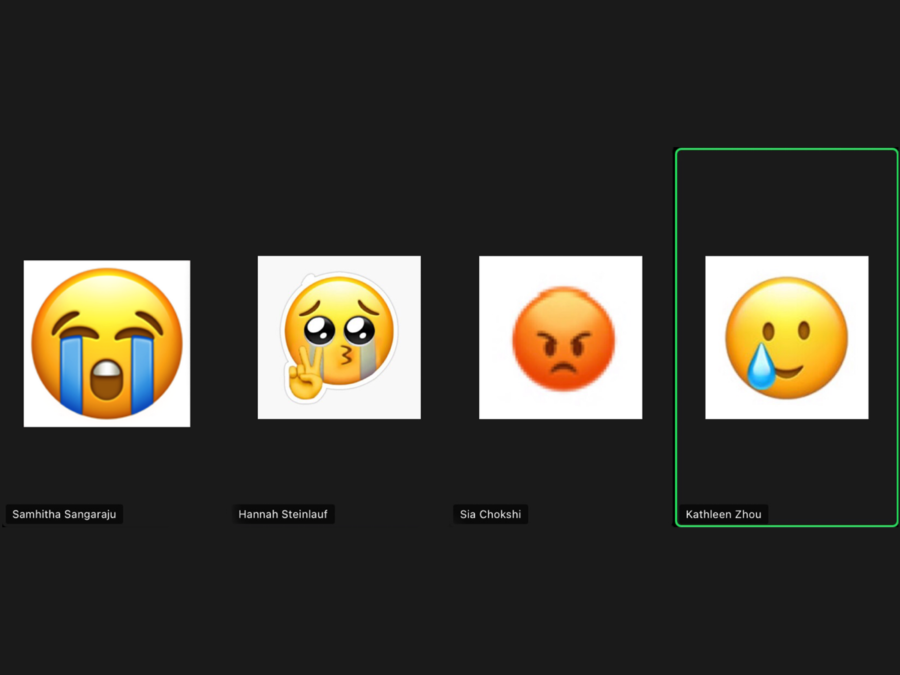

Four students sit down after a long day of revising articles for The Eagle’s Eye and get ready to write an editorial together. Four students, bursting with ideas, excitement, perhaps even anger, send a flurry of text messages back and forth, discussing ideas and possibilities–there is much to discuss, ranging from national failures to municipal issues. They are itching to write, yet nothing appears on the blank document.

They are stressed, overwhelmed, and overworked, run down from the pressures of school. Politics, human rights, feminism–all topics they could go on about for days, and yet school completely encompasses their lives, leaving them unable to speak on subjects they have much to say about. Exhaustion is our story, and undoubtedly the story of many others too.

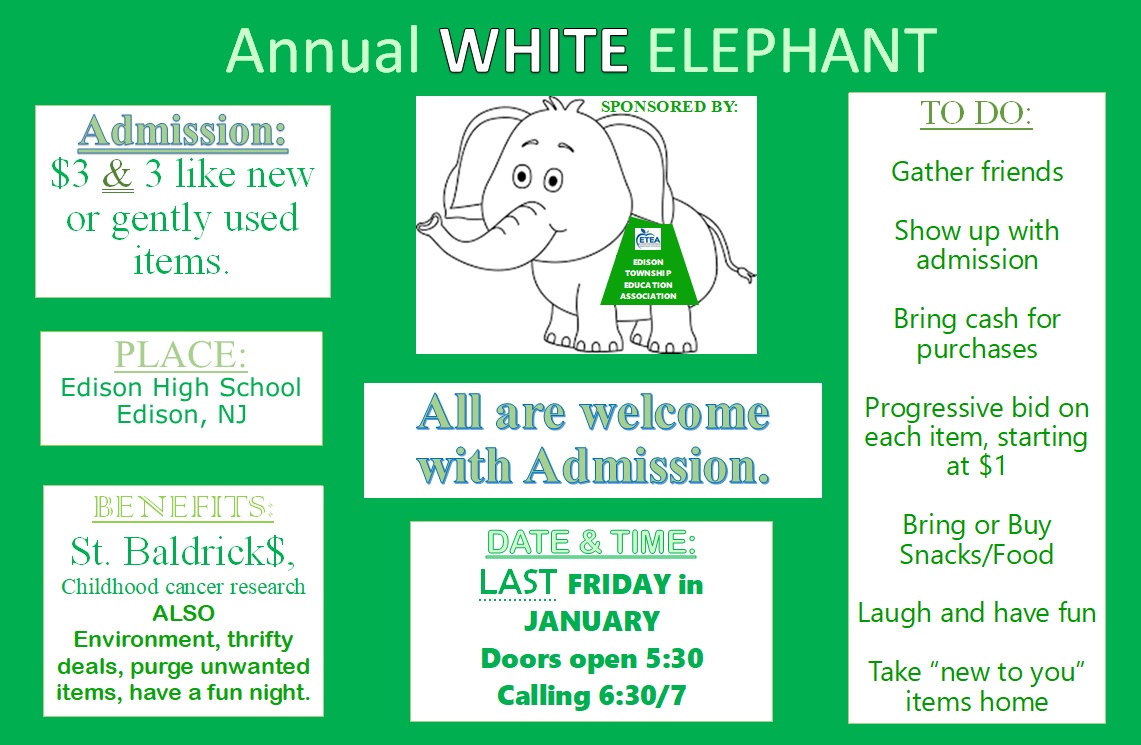

Let’s face the elephant in the room: Edison’s transition from physical to online school is terrible. In a sentence: the system right now is normal school crammed into an online format, not online school. The school district has attempted to keep as normal school the same online: the amount of assignments and tests given, the weight of grades, the grading system, the schedule. And the expectations.

Currently, the amount of schoolwork given out is just the same, if not more than before. Assignment after assignment, test after test, project after project–there’s an endless stream of work we can’t escape. While this arrangement was somewhat manageable–not efficient, manageable–during in-person school, during an unprecedented pandemic, the volume of “homework” combined with school puts far too much pressure on students. We already know the high volume of tests and assignments is stressful during regular school, but when we look at the way studying and homework sometimes doubles our already six-hour plus screen time, we see that the amount of work assigned is excessive.

And as a result of this additional stress, the grading system should change to accommodate that. The Board of Education most likely kept our current grading system because they believed a hybrid model would return us (somewhat) to “normalcy,” but the fact of the matter is that “normalcy” needs a change. Students should not be having panic attacks over a test. Students should not be losing hours of sleep to write an essay. Whether it be the grade boundaries or grade weighing, there needs to be a change.

Let’s speak about expectations, too. Why do we have to perform at the same level as we were pre-quarantine? It’s asinine. The score required to get an A- or a B+ is the same as before. Why are these boundaries unadjusted? They should be changed. The same amount of effort doesn’t necessarily equate to the same result in this time period because online schooling does not work for most of us.

“…there needs to be a change.”

What’s worse is that these issues could have been avoided earlier on had the Board of Education actually asked for, and cared for, our opinions. We’re not even sure they care for the teachers’ because teachers have asked for concessions since the beginning and were granted little. Take block scheduling, for example. That was a change, and a welcome one at that. For many students, it meant that they could keep their current job hours. For others, it meant a welcome reprieve from the hustle and bustle of 45-minute periods. And they changed it before we tried it, without sending out polls or asking for the general public’s opinion.

We speak for the student body: our eyes burn, our backs hurt, and our heads ache. After spending six hours staring at classes full of tiny people, all looking just as tired as the next, students find themselves forced to sit in front of the computer for hours afterwards, attempting to finish “homework.” Whatever this is, it isn’t working. At a time like this, what is homework? Every piece of work we do now is at home, so what can be constituted as “homework”? The work done outside of Zoom? Students nowadays are so concerned about their grades, a reflection of the increasing academic pressure of high school. But students complete this “homework” nonetheless, and every extra hour of work assigned is an extra hour spent hunched over a computer, wrecking our eyes and backs for the sake of schooling.

When the boundaries between home life and school life are dissolved like this, the comfort of “home” leaves us. For many of us, our bedroom is both our school room and our living space. And when we begin to associate home not with reprieve but with stress, we lose that comfort. And guess what happens when we lose that comfort? We get even more stressed. Stress hinders productivity, which in turn leads to make up work, which in turn leads to more stress and the cycle continues. Homework is supposed to be a tool to help us learn, not something that hinders us.

Let’s talk about how the pandemic has affected students’ mental health, too. The situation is bleak and school certainly isn’t helping. We’re sad. You’re sad. It’s a constant sadness that you can’t escape because your room makes you sad because school makes you sad and school is in your room. The school pretends to care, with its agenda of “health comes first” and “mental health is important,” but fails to be effective. Students with health problems fail because they have six absences. Students with depression fail because they have no motivation to join a Zoom call, and somehow that reflects their grade more than the work they do. How is that fair?

Online classes have disrupted the lives of students and faculty, and continue to complicate education in these unprecedented times. So what can be done to try and alleviate some of this school day stress?

Improved communication between faculty and students would be a huge relief to students. Many may feel uncertain on the topics they are being taught, as the online school set up does not allow for the best learning experience. Others might understand information, but need help furthering or applying their skills. If teachers are able to find more one-on-one time with students, or give extra resources such as videos to supplement their learning, a student may develop a more well-rounded sense of their studies. Teachers should also loosen up strict deadlines, such as having exams due at the exact end of the period. The stress of finishing early to upload a hand-written test may inhibit students from performing the assessment at their full potential. Above this, the Board of Education should continue to push out updates to schools in an orderly manner. Many students feel lost when it comes to the changing schedules and guidelines, and teachers do not seem to know the next step themselves. The uncertainty within our school community promotes this stressful environment we all find ourselves in. If consistent and concrete Board of Education decisions can even ease this tension the slightest, we will all feel its effects.

Additionally, a more accommodating schedule can help students drastically. Think back to the students with depression who could not motivate themselves to get out of bed. If they had a few days a week where attending Zoom was optional-not mandatory, not only would their grades do better, but they might be more willing to join the Zoom on mandatory days.

Students have been calling for a later start to school day for years. What better time to take advantage of this request than now? There are no implications for starting school at 9 o’clock instead of 7:40. While in person, this raises questions about ending time and after school activities. But a pandemic provides the best solution to both of these: a small percentage of students are in-person, and after school activities should not be occurring at their full capacity. Why not give students a break, and let them wake up later?

These issues are not just clear in the lives of students, but in those of teachers as well. On a constant basis, students watch as teachers face the same issues in almost the opposite way. If they do not supply students with the correct number of assignments, their credibility and capability is questioned by parents. If they do not grade fast enough, they are labeled incapable of their jobs, and sent difficult emails. Though we may expect teachers to be fully available all the time, students do understand the faculty has a life outside of the school building; one filled with their own children, second jobs, social commitments, and household chores. When does it become enough? Students are not adapting in this situation, and teachers alone may never be able to fix the issues students face behind the screen. There must be a balance, both for teachers and students, in which both groups are not stretched to the ends.

The pandemic raises questions of mortality–a grander meaning to life. There’s no denying that we’re in fearful times. Questions of rising racism, national division, violence, politics, and human rights serve as an anxiety-ridden backdrop to an already fraught situation of isolation and loneliness. And yet, life must go on like before, right? So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.

Except moving forward apparently means stagnancy. “Forward,” to students and teachers alike, means being subject to the frivolity of schoolwork amidst the rising chaos. What happens when the boundaries between school and daily life are blurred? Declines in mental health, declines in grades, declines in performance, declines in learning. Students and teachers alike are set up for failure right now. Modifications to curriculum, workload, expectations, grading–these should not be privileges. They’re basic human considerations.

In conclusion: the student body needs a drastic change of perspective. And perhaps leadership.