AP African American Studies: Is EHS Answering The Long-Awaited Call To Action?

March 22, 2023

At EHS, Ms. Karen Kirkpatrick teaches both an Introduction to African American and Diversity studies class. It seems as if a ball has begun rolling, and the College Board is sitting at the end of the hill with their brand new African American studies course.

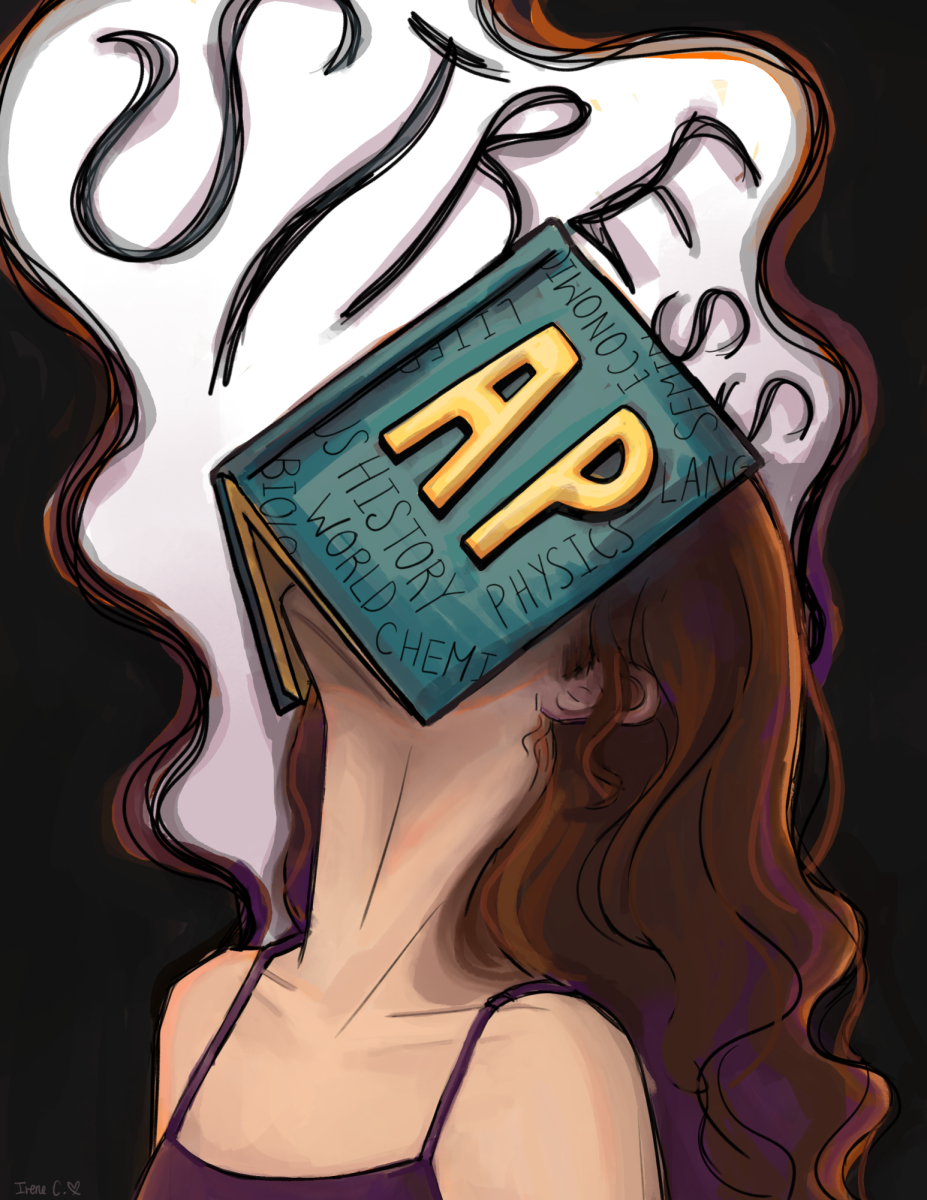

According to the College Board, the new course was created in collaboration with African-American studies professionals to create an AP course that highlights the contributions of Black Americans to society and history. AP African American Studies will dive into African-American culture and history by exploring the contribution of Black people in America to literature, arts, humanities, political science, geography. By the 2024-2025 school year, the AP course and test will be available to all schools in the nation, including EHS.

The course will consist of four units: “Origins of the African Diaspora,” “Freedom, Enslavement and Resistance,” “The Practice of Freedom,” and “Movements and Debates.” The first unit will cover African civilizations through a variety of primary sources predating any interaction with Western civilization. The second will take students through the transatlantic slave trade all the way to the post-Civil War time period, while the third will examine the Jim Crow era, the Harlem Renaissance, and other social and cultural movements. The fourth unit involves relatively more recent advancements such as the Black Power movement and Black Lives Matter, and is mainly characterized by the 1,200-1,500 word research project that the College Board will require of students.

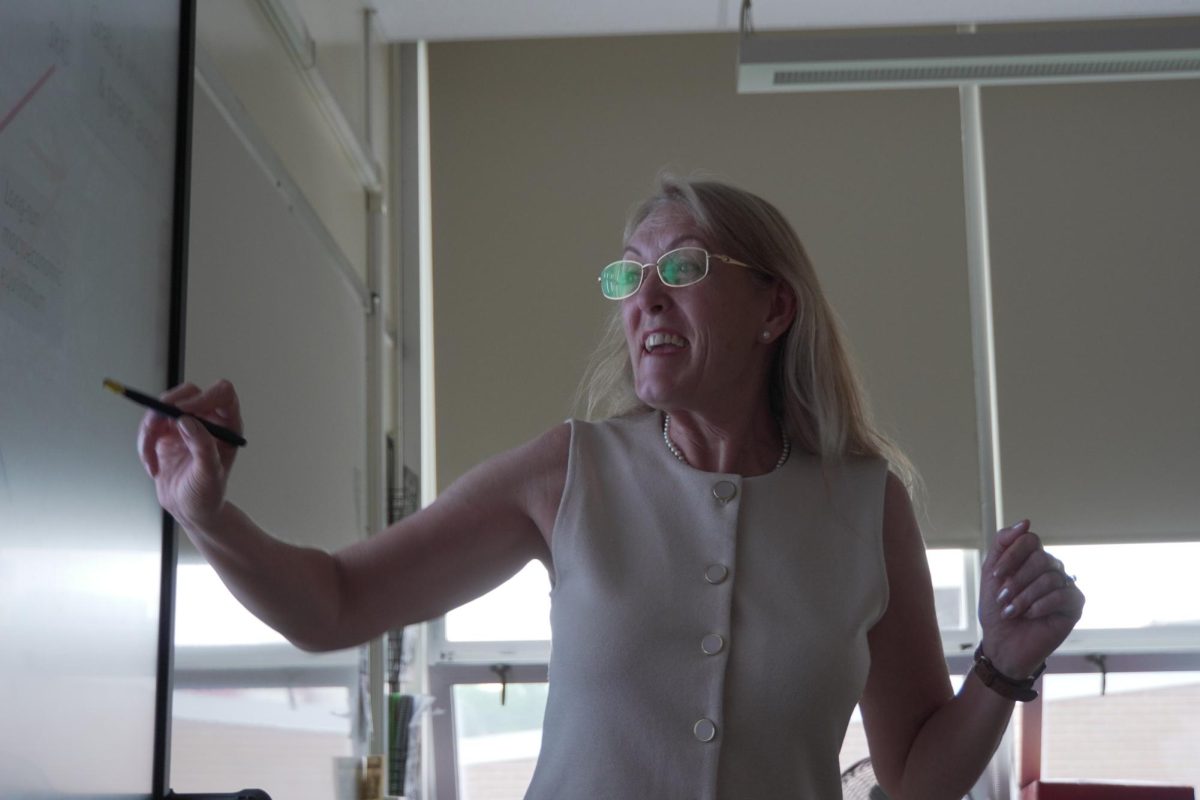

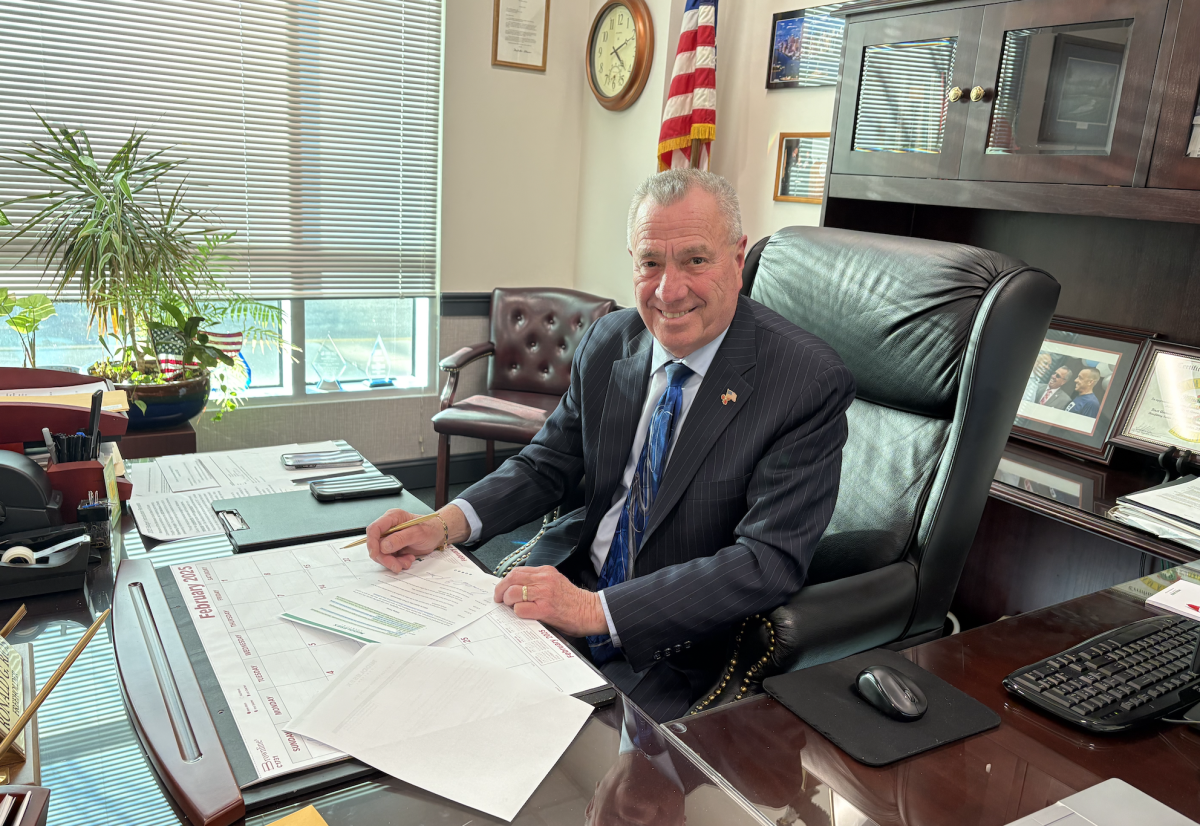

“Just speaking from my own personal experience, growing up in this county, I was not really exposed to any African-American literature until I got to college. And, I feel like I should have been exposed to more diverse texts earlier than I was,” said Mr. James Napoli, a 9th grade Honors English and AP Seminar teacher. “ And I do think that there are teachers here [at EHS] who are extremely qualified and capable of teaching this program or any other program that offers diverse literature, text, and history really well.”

Other teachers still acknowledge the need to highlight African-American history and voices, but believe that it will be accomplished through gradual changes, instead of a curriculum revamping.

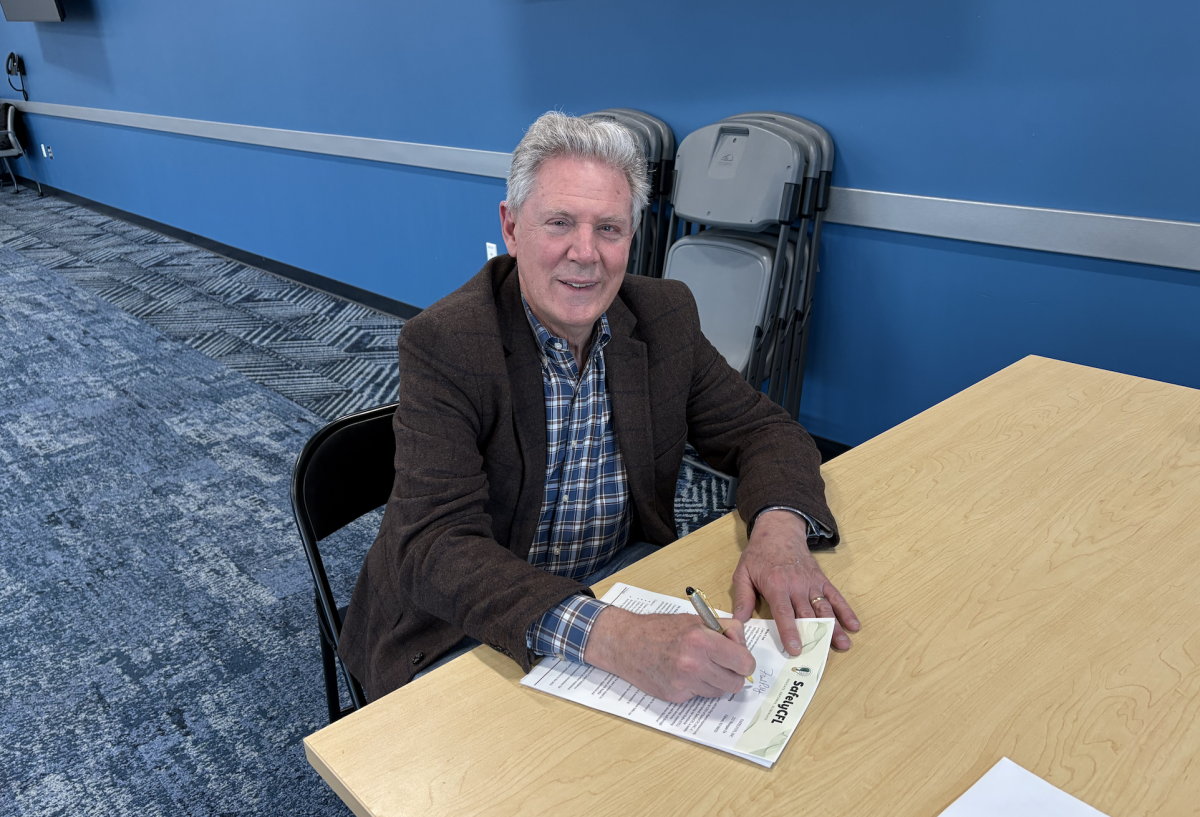

“Within US history, you emphasize the contributions of marginalized groups that have been largely ignored in the earlier telling. I don’t think you need to redo an entire curriculum, but you include the contributions of African-Americans, women, and other marginalized groups in history. You don’t want one side writing the curriculum for history,” said Mr. Michael Korneski, a US History teacher.

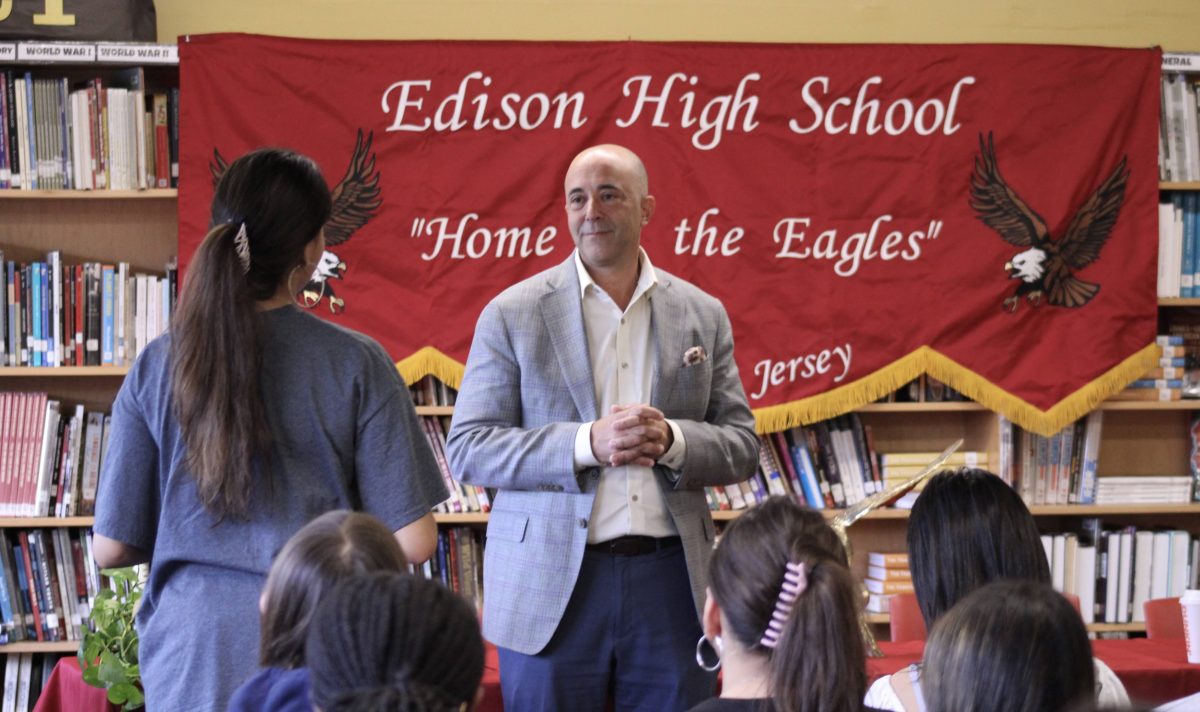

However, it seems as if EHS already offers something similar. According to Mr. Mark DiGiovacchino, social studies supervisor, EHS has been offering an Introduction to African American Studies semester course for the past two years with seemingly similar topics— “America and the African Diaspora,” “Diversity of African American Identities,” “Dehumanizing Policies and Narratives of Resistance,” “Reshaping a Fragile Democracy,” and “Modern Resistance, Celebration, and Activism”— just on a shorter time frame.

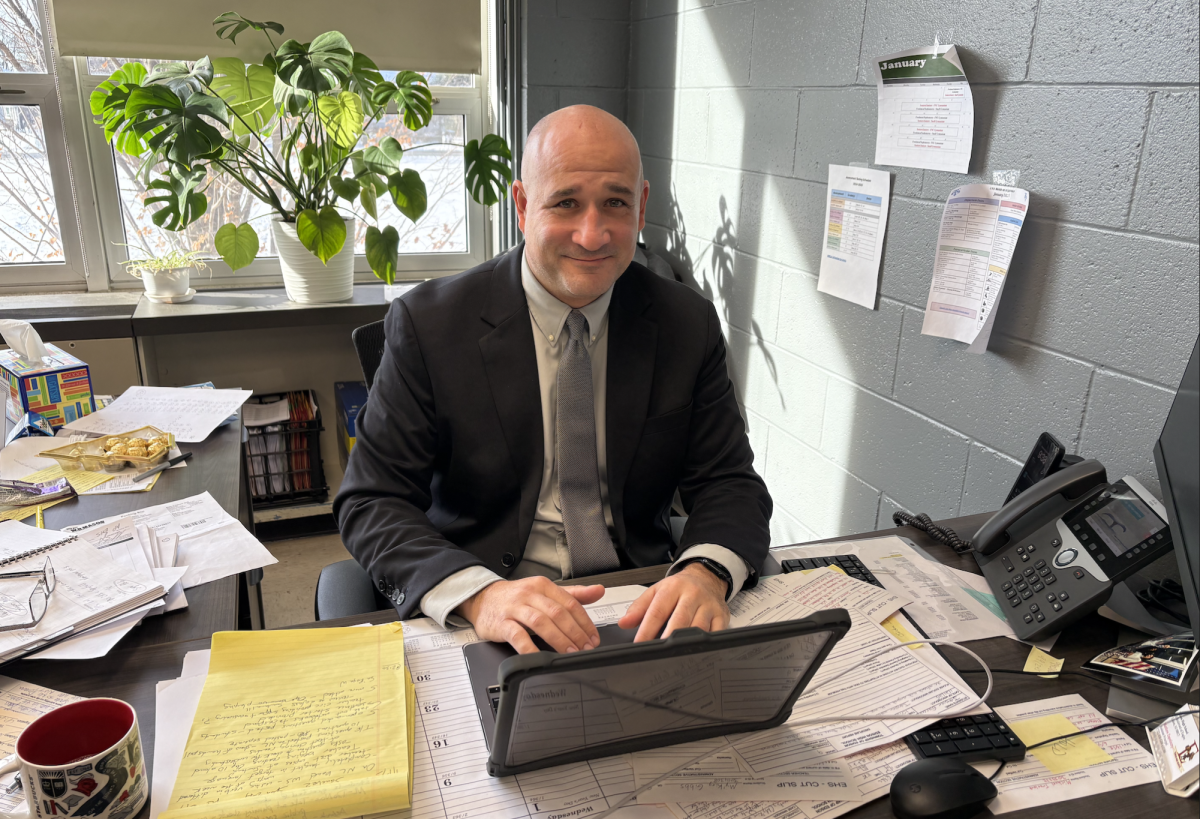

“It’s not a matter of if the subject matter is something we want to offer to students. I mean we have known that for a while. It’s more about what form it looks like,” DiGiovacchino says, explaining that while EHS will be sure to offer an African American studies course, investigation into the master schedule, class sizes, and staffing need to be conducted before a decision can be made on the AP course. This sentiment is in debate.

After a draft curriculum of the course was leaked, according to the College Board and US News, conservative politicians such as Florida Governor Ron DeSantis, criticized the subject matter for its apparent bias and misinformation and threatened to ban the course in all Florida public schools. Most opponents were concerned by the fourth unit which initially covered topics such as anticolonial movements, Black Power, secondary sources regarding the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement, and writings of Kimberlé Crenshaw, a leading voice in Critical Race Theory. They also claimed it violated a Florida state law, which gave the state government the power to regulate the teaching of race-related issues. Following the official release of the curriculum on February 1, observers noted that these topics were missing from the curriculum.

“There probably needs to be some consistency or some foundational piece, but I don’t know if politicians should be telling students what they can or can’t learn, can or can’t read, or what teachers can or can’t teach—as strongly or forcefully as they are doing now or at least attempting to,” said Napoli. In the current-day classroom, with lively discussions of censorship and free expression, it is often debated to what degree figures of authority have power over the education of the next generation. The suggestion is that by controlling curriculums, politicians might indirectly control the thought processes of students, hindering critical thinking and introducing bias into curriculums.

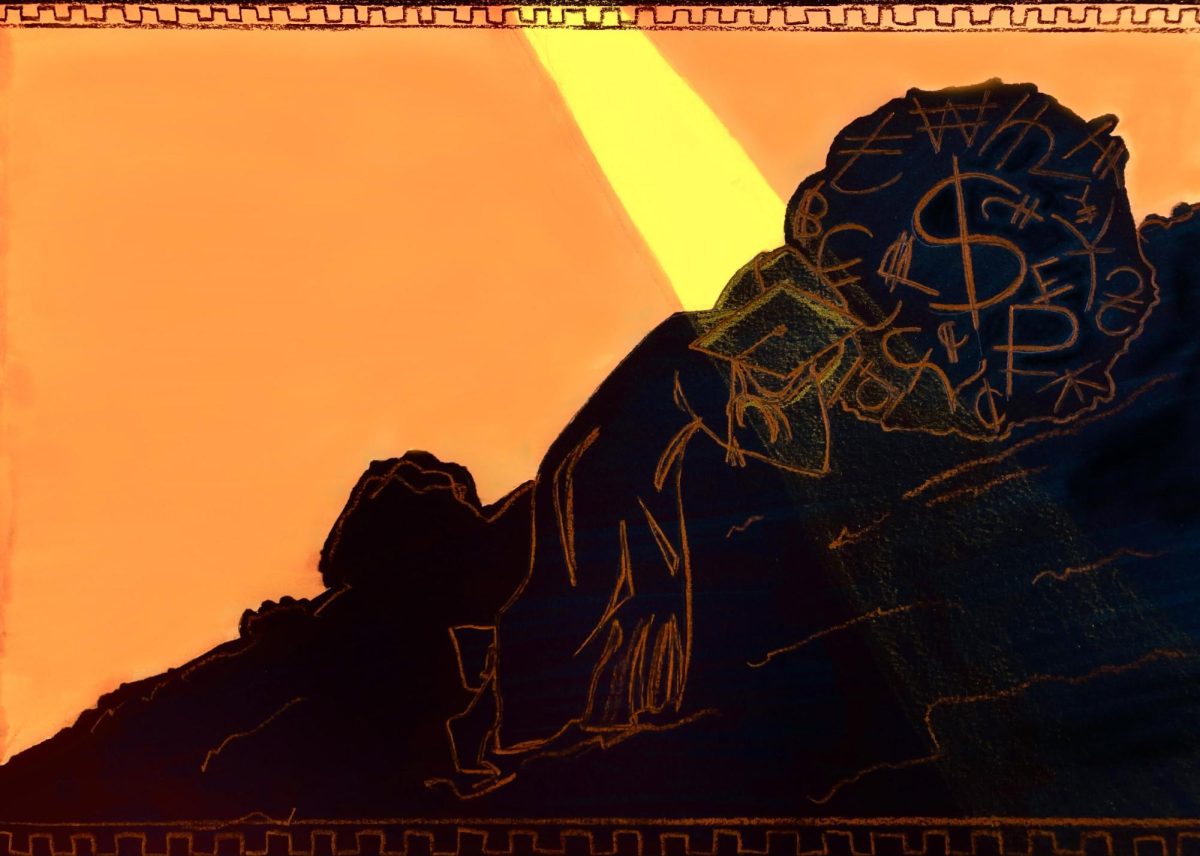

“Black-Americans have planted very deep roots in America. Many of the national monuments were built by slaves and slave descendants,” said Ms. Charese Johnson, the Black Student Union advisor and English teacher. “People must realize that before we were brought to this country, we were kings and queens. We were doctors and chiefs. This new curriculum not only fails to explore the history behind the history, but it also looks to water down or cut out altogether education about controversial issues that Black Americans deal with on a daily basis, like LGBTQ issues, the BLM movement, [and] mass incarceration.”

On the other hand, the NJ state government seems to passionately encourage diversity in Social Studies education. DiGiovacchino explains that the NJ Amistad Law, circa 2002 and named after an 1800s ship commandeered by slaves, ensures that schools deliberately teach African American studies. It has also set a precedent for several laws that emphasize teaching about LGBTQIA+ Americans, Americans with disabilities, and Asian-Americans and Pacific Islanders.

“Much of our curriculum already included the content that would fall under the purview of those laws. But, the nice thing about those laws is that it gives schools the impetus to go deeper and find topics and stories that might not be in The American Pageant [textbook], for instance,” said DiGiovacchino.

He also stressed the importance of ensuring that educators know how to translate a diverse curriculum to a classroom that is accepting of diverse voices. Mainly, he highlighted the importance of professional development workshops, such as the ones offered by the NJ State Bar Foundation on teaching African American history.

Johnson agreed that EHS is, in fact, doing its best to ensure all perspectives are represented through works from a variety of cultures, instead of sticking to a Eurocentric curriculum as many do right now.

So, while the AP African American Studies course has been met with mixed sentiment throughout the United States, educators at EHS acknowledge the importance of the subject matter, and hope to foster an inclusive environment, whether it be through an AP course, a semester elective, or just the diversification of reading lists.

“That is the goal: to make sure that the perspective of all students of all backgrounds are recognized in our courses,” said DiGiovacchino.