Brown Boys: Victims of Identity Crises or Perpetrators of Cultural Appropriation?

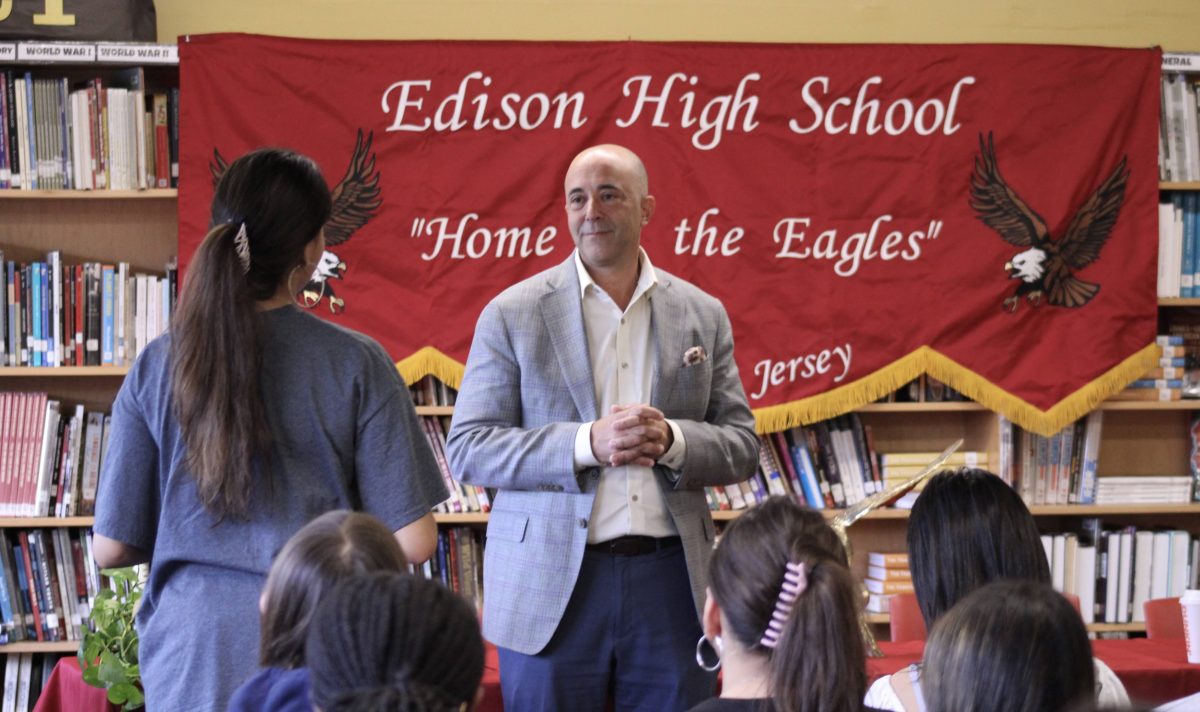

A diverse population and an influential pop culture raises questions about shaping identity at EHS.

April 13, 2023

While scrolling through Instagram stories, it is certainly hard to miss the sheer amount of photos of our mostly South Asian peers at the tri-state area concerts for NAV’s recent Never Sleep tour. NAV, an Indian-Canadian himself, is well-known in the rap genre sphere for his silky vocals and Afrobeats. Beyond his commercial success, however, NAV has been the poster boy for the recent prevalence of an increasingly controversial issue amongst the South Asian Western community: a divisive stance on brown boys.

In our own backyard, it is not uncommon to see South Asian boys sporting gold chains and heartily singing along with Black rappers such as 21 Savage and Playboi Carti. However, harmless fun turns sour as such “brown boys” begin to rap the N-word and exploit African-American vernacular English (AAVE), throwing around excuses such as, “it’s just a song” and, “I’m brown, too.” In the halls of Edison High itself, you can hear a plethora of racial slurs, and South Asian boys, so-called descendants of suburban Edison, claiming in AAVE, that they live in the “hood.”

So, are brown boys allowed to say the N-word?

The short answer is no, they are not. The long answer is still no, but let’s explore why they felt they could.

Within an EHS classroom, brown boys crowd around the back of the class, snickering, as teachers touch base on racially sensitive topics. In their eyes, they have the right to do so, as they are basically black. Yet the moment they return home, their blaccent is dropped, as they nod along with their traditionally conservative relatives — playing a game of which minority did it best.

The use of AAVE, whether it be casually or in a conscious attempt to appear less brown, fails to acknowledge the origins of the dialect and the ill-placed negative connotations surrounding it, and thus indirectly disregards the Black community. Such behavior is analogous to wearing a blaccent as a costume only when the user sees fit. Additionally, comparisons between comfortable, residential communities such as Edison’s Durham Woods or Village Commons to ghettos, products of gentrification and systemic racism, are both ignorant and abhorrent.

Abuse of AAVE and adoption of other forms of Black culture are clearly apparent in the modern brown boy. Therefore, for some, it becomes harder to draw the line between cultural appreciation and cultural appropriation. With the popularization of African-American culture and poor South Asian representation in music and television, the line only gets muddier.

Recent popularization of African-American culture— AAVE, hip-hop, box braids, etc.— as well as the portrayal of nerdy, weak South Asian characters in Western media play key factors in brown youth feeling not only inclined to, but justified in adopting Black culture. Rather than be a foreign, social outcast, brown boys want to embody the toughness and masculinity seen in Black male archetypes.

Nowadays, we see brown boys at the feet of Kendrick Lamar and Jay-Z, old-school classics in the hip-hop and rap genre. These rappers often represent the gang/ghetto struggle, often connoted with twentieth century Black culture and history. Whether this almost parasocial devotion to Black artists is a respectful appreciation or a subconscious outlet to defy the systemic lack of South Asian representation is entirely situational, and often difficult to discern.

Part of the appeal of hip-hop and African-American culture in the eyes of current South Asian-American youth is our own lack of satisfactory representation in Western media — specifically in children shows. With characters like Baljeet in Phineas & Ferb and Ravi in Disney’s Jessie, brown kids who grew up during the late 2000s and 2010s had no solid form of realistic South Asian representation. Both Baljeet and Ravi have thick Indian accents, are brainy and aloof, and, although lovable, are the makings of social stunts and rejects. In other words, these characters are the pure manifestation and perpetuation of brown stereotypes.

Even now, with teen shows such as Never Have I Ever playing on loop in South Asian and non-brown homes alike, we still see the disappointing embodiment of Indian stereotypes (specifically amongst males) in our favorite main characters. Take the show’s characters, Devi and Des. Although Devi addresses her lack of connection with her Indian culture and Hinduism multiple times throughout the show, she still represents the South Asian stereotype by being a hopeless romantic and school-obsessed nerd. Nevertheless, she is given the opportunity to grow into a dynamic character, while her temporary brown love interest, Des, is forever deemed a nerdy mama’s boy.

Compare these derogatory Indian clichés to Western representations of Black and African-American people. The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air and Yo! MTV Raps were both highly popularized shows throughout the 90s. Although arguably outdated, the shows still hold the typical stereotypes we see in American views of Black culture: hip-hop and a hood-like toughness. Note that these stereotypes evidently do not hold true in the real world and are not only antiquated, but simply wrong. Where these wrongful stereotypes come into play is their clear differences when juxtaposed with South Asian media standards.

Taking this into consideration, the origins of both South Asian internal and systemic racism is hard to pinpoint, but we can trace it back to the first instance of South Asians in the United States. At the turn of the twentieth century, Indians began settling on the West Coast of the United States, seeking out economic opportunities. The majority of the migrants were Sikhs, a religious minority from India. Many worked in mills where they had to assimilate to Western culture. Nevertheless, most Sikhs refused to cut their hair or relent on wearing their turbans, clear cultural indicators of their religion. Around the same time, many communities began ousting South Asian workers, and in 1907 even saw the establishment of the Asiatic Exclusion League (AEL) to expel Asian workers. Fortunately, in 1947, Congress finally passed a bill for Indian naturalization.

With this new change in policy came the birth of the Northeast’s own “Little India”: Edison, New Jersey. Many immigrants who had previously resided in the Big Apple found their way to Edison in search of the American Dream of property ownership. Around the 1950s and 60s, Indian merchants began purchasing dirt-cheap strip malls along Oak Tree Road and various other streets in Edison, serving as a precedent for current-day fan favorite shopping sites such as Apna Bazar and Sukhadias.

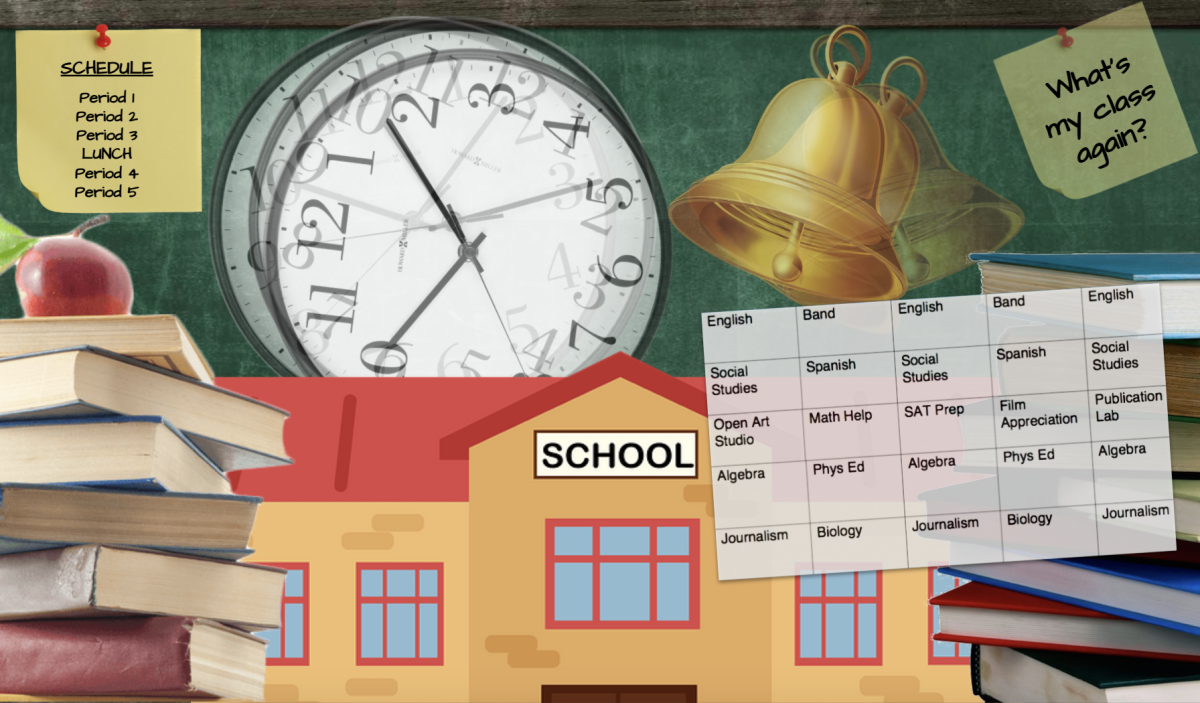

Nevertheless, some might argue that Oak Tree Road is a (figuratively) walking stereotype. Oak Tree is the embodiment of Indian uncles with thick accents and aunties forcing down sweets often seen on television. The stapled advertisements for tutoring centers and SAT prep go to show that Hollywood depictions were right! Those Indians are just IT nerds!

Note the sarcasm.

Inside the residential communities atop these cultural hotspots, you can find several South Asian schoolboys claiming their neighborhoods are the “Indian ghettos” or “brown hood” in a last-ditch, wholly distasteful effort to combat the derogatory stereotypes that make them “monkeys” and “tech support.” Oftentimes, these brown boys run in packs, bubbling with a sense of misfounded camaraderie. They use terms reserved for the Black community to fondly refer to each other, and establish a social hierarchy hinging on who appears the least Indian and the most cool, masculine, and even African-American.

So, regardless of how hard our parents and grandparents fought to preserve our roots, it seems as if society has turned us against them.

Now, in spite of the stereotypes present in television or the some-might-say tacky, physical reminder of our origins, otherwise known as downtown Edison, the South Asian struggle is one starkly different from the African American struggle. Similarities in skin tone, the nature of both groups as minorities, or the isolation felt by the brown community do not excuse exploiting another’s culture and history for the sake of one’s own comfort.

It is key to note that while this article has discussed brown boys in its majority, South Asian females such as the once-reigning YouTube comedian, Lilly Singh, have made equally unjust claims to Black culture. For instance, Singh spoke of coining the term “bawse” and was often characterized by her box braids, typically worn by African-Americans as a protective styling choice.

At the end of the day, brown boys, although the indirect results of a niche form of identity crisis, continue the vicious cycle of cultural appropriation. While we must condemn those that appropriate Black culture as a South Asian, we must also work forward to incorporate each other’s cultures in a respectful environment. So, the next time NAV uses the N-word, remember the history and cultural cultivation behind the word before you mouth along with it for your next TikTok.

Authors’ note: Any use of the term ‘brown’ in this article is in reference to the South Asian community.